Some time ago, I recorded my first podcast on accents and the"Voldemort effect". Here's another post/ramble, unedited, heart-to-mind, mind-to-heart talk, of this complex feature of attaining, sustaining, and more importantly, owning and loving your accent.

It was inspired by my teacher trainees in their last year, and the challenges I find while teaching these advanced students.

Usual pre - listening warnings (I am a teacher, after all, and I am my own teacher, as well):

☂I have mispronounced "Patronus". I should have probably pronounced it: /pə'trəʊnəs/. ☂Plus, there are a few choices in word stress, nucleus placement, tone and tonality which I would have made differently. ☂A few " dysfluencies" as well, sorry to say!

As usual, many of these posts emerge as "reflections in passing", almost through a "stream of consciousness" technique, and editing this post would have meant spoiling the spontaneity of this moment of realisation, and thought.

So here it goes. Hope you will enjoy it.

martes, 19 de mayo de 2015

lunes, 11 de mayo de 2015

Pronunciation, Phonesthesia and Realia: The case of the STRUT vowel (Part 2)

In my latest post, I compared General British STRUT and its variants to Riverplate Spanish /a/. I reviewed some articulatory and also acoustic features, and I also went over some basic notions of Speech Perception theories. I established that many of my Riverplate Spanish learners may associate English /ʌ/ with their Spanish /a/ "magnets" and may, thus, find the differentiation between both vowels challenging, both for perception and production.

(BTW, apparently, the differentiation between English /ʌ/ and other vowels appears to be quite an issue for many speakers of English as an L1 or L2, as Ettien Coffi (2014) reveals in this paper from the Proceedings of the 5th Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference - page 11 onwards)

In this post, I would like to present some of the tips & tricks I have collected over the years (and I will try to acknowledge my colleagues' contributions whenever I can!). My claim will be that many "tips" do the job when they help create an image of the L2 sound which may help the learner steer away from their L1 quality, and that this may not necessarily just be reliant on making the right articulatory movements.

This is why some of my suggestions will draw on creating "mental images" through the contributions of Phonesthesia, and Realia; images which should appeal not only to visual aspects, but also auditory, and emotional resources.

***

A few definitions first:

Realia refers to the introduction of real-life objects in the classroom, to make the learning experience of certain concepts and routines more vivid. This technique also enables students to engage all their senses and learning styles. We can introduce actual objects, or we can create virtual situations that may allow students to experience similar emotions and actions as those recreated in the real situations.

(You can get some teaching ideas on using teaching aids in the TEFLSurvival blog, and the BusyTeacher website.)

Phonesthesia refers to the analysis of "sound symbolism". It basically studies how clusters of sounds may center around lexical sets that express similar meanings. So for example, in the Dictionary of Sound by Margaret Magnus, you can find a number of STRUT words that could be related to "puffy things": plush, fuzz, fluff, cuff, muff, ruff.

This reminds me of a poem by Tony Mitton, called "Fluff"

What's this here?

A piece of fluff.

I don't know where I get this stuff.

I'll blow it away

with just one puff.

Huff!

There. That's enough.

So the combination of vowel /ʌ/ and the /f/ quality, reminiscent of blowing, creates this "puffy" effect of fluff and makes the poem lovely for oral performance, and effective!

***

As a College student, I had a hard time fine-tuning my STRUT away from my Spanish /a/. I was given instructions, I knew I had to drop my jaw, but still, it sounded pretty much like my own Spanish /a/. (Mind you, my friend and colleague Prof. Francisco Zabala has found that the STRUT quality as an allophone is present in many Spanish combinations of "a" + sound /x/, as in "caja".) And I see my students at Teacher Training College producing a similar type of Spanish /a/ sound. So after a few tries, after watching native speakers of English produce their STRUT sounds, analysing the way this jaw-dropping takes place for this sound, I came up with the first articulatory tip that worked for some of my students:

"Keep to the railings of the mouth". I asked my students to imagine that each of the two sides of their lips, or the corner of their mouths, had a vertical railing, and that there should not be any smiling, as it would defy the railings of the mouth, and that the articulatory movement should be downwards, not sidewards. I could not help thinking of these special types of puppets ventriloquists use:

|

| Image credit: David Noah. Flickr:https://www.flickr.com/photos/davidnoah/5170268541/ |

With this idea in mind, in one of my lessons, students were asked to place their fingers in the corners of their mouths in the puppet-like manner above, and look at themselves in a mirror/front facing camera of their mobile phones while producing STRUT words, trying to avoid a smile (which was tough, as they were having fun!).Therefore, this sound became the "puppet" sound (and for older Argentinians, this was the "Chirolita" sound, after a well-known ventriloquist in Argentina).

This articulatory tip did the trick for many students, but yet, not all of them really got to acquire a close quality; many students still produced a much fronter, or sometimes, opener vowel.

So I resorted to phonesthesia, and I thought of a few words I associated with the STRUT quality. By repeating the STRUT vowel to myself in isolation, I came up with these words (and a few others, after trying the marvellous Sound Search tool in the Cambridge Pronouncing Dictionary CD-Rom!)

- Things falling and making noise: thud, plunge

- Unpredictable, shocking: abrupt, blunt, rough

- Pushing, stabbing(?): thrust, chuck, cut, nudge, punch, butt

(BTW (deviation alert!), as a Miranda Hart fan, I could help laughing at myself while repeating these words!)

So with some groups of students, I tried playing around with the words above, getting into the mood of things "falling" or happening "abruptely", which acts in much the same way the downward movement of the jaws does, like a small "bite", even.

Encouraged by the success of this tip for some students, I started thinking about the realia of "emotions", the "tone" that this sound evoked in me, and I could not help feeling "dull", "disgusted" or "miserable", as with these words:

- love

- money

- you suck!

- duh!

- yuck!

- f*#k

And I said to myself (and forgive the vulgarity of it all!), "what makes you suffer? Love, or money?". So I asked my students to think about their most "miserable" feeling, place themselves in that "sad place" (a bit like many actors do), "pull a miserable face" and go for /ʌ/ .

|

| Credits: http://i3.mirror.co.uk/incoming/article4311979.ece/ALTERNATES/s615b/Kim-Kardashian-and-Kanye-West-arrive-for-a-dinner-at-Hakkasan.jpg |

When using this strategy a few years ago, a student came up with the memory of losing a match as a kid, and remembering his father's disappointed reaction (a very sad place to go to, if you ask me!). So we worked on that emotion, and we created a situation in which a very stern father or mother would push their son or daughter to win a race. And I came up with this terrible (!) poem/song, with a "run, run, run" chorus to the melody of Pink Floyd's "Run like Hell". It does sound like a bitter and very dark poem, but as a dramatic technique, it did the trick!

In one of the lessons where I tried the poem, students worked in two teams, with one group acting as an audience, singing the "run, run" Pink Floyd chorus, and a second group "mumbling" the words of the poem as they all pictured the race and their son running. The "little play" that resulted of this poem reminded me of Hermione in the audience uttering the Confundus charm and Harry saying "Come on, Ron" in a sort of low murmur (Deviation alert #2!):

***

Somehow this idea of a "miserable" STRUT sound has been the most effective tip to help my students provide a version of /ʌ/ that drove them closer to a quality different from their Spanish /a/, and also from the "Happy, cheerful, /æ/" and the "Relaxed, cute, awwww-like, /ɑ:/":

***

As with everything, you can find your own way of adapting these tricks for your own lessons, taking into consideration the "classroom management" factor, because let's face it, pronunciation work may create a bit of a mess in the classroom!

And of course, as Adrian Underhill claims, multisensory pronunciation learning is the key. Building one's own proprioception, and supplementing this with mental, auditory and emotional images should, in some way or other, contribute to the uniqueness of our learners' styles and processes. As I always say, what may work for one student may not necessarily work for the other! (Another piece of evidence for the "messy" nature of pronunciation work, sorry to say!)

***

Final thought: It is funny that many of the nice things of life may also take STRUT, and they don't seem to "fit" with with sound. What shall we do about

love, fun, feeling chuffed, abundance, bubbles ...and maybe, money?

I leave that to you!

Etiquetas:

contrastive analysis,

ELF,

ELT,

errors,

feedback,

interlanguage,

motivation,

perception,

practice,

production,

pronunciation,

psycholinguistics,

resources,

tips,

tricks

viernes, 1 de mayo de 2015

Pronunciation, Phonesthesia and Realia: The case of the STRUT vowel (part 1)

With the release of Adrian Underhill videos, I can now re-live some of the presentations of the IPA that my Phonetics tutor and trainer, Prof. Graciela Moyano, introduced when I was a first year student at College. It's just brilliant to go back to those moments of discovery of how our articulatory system works.

I have completely embraced Adrian's belief and knowledge that "pronunciation is physical", and this motor side of pronunciation and our awareness of articulation through the different "buttons", as he calls them, is essential. However, out of his presentations, my independent reading, and my own teaching style, I have found that part of the process of acquisition of L2 features also lies on the images that we make of what the L2 features sound like.

Over the years, I have discovered that part of the fine-tuning processes we need to carry out to learn the sounds of L2 also involve affective aspects, including our own affective memory, and feelings. I have experienced situations in which students appear to be making the right articulatory movements, and still, there is something in the quality of the sound that does not "sound right". And in those cases, what I noticed is that it is the recourse to mental and affective images related to the sounds that appear to do the trick, rather than just the right lip or jaw position.

So in this post (which is, obviously, not a report on experimental research, so don't expect it to be so!), I will be going over a few techniques that I have used to include phonesthesia and realia in my pronunciation teaching. My focus this time will be on the STRUT vowel, /ʌ/, one which gave me a lot of trouble as a learner!

I will be covering a few different theoretical and practical areas on this post, which is why it will be divided into two:

Part 1:

Collins and Mees (2012) have defined STRUT as a central, open-mid checked vowel, and admit a certain degree of variation, but especially in terms of fronter qualities. In much the same way, Mott (2011:117) describes STRUT as being "slightly forward of centre, just below half open, unrounded".

The abovementioned authors would then place STRUT somewhere around these areas:

***

Riverplate Spanish Vowel /a/

Spanish /a/

(American) English /ʌ/

***

There appears to be an interesting similarity between Spanish /a/ and GB English /ʌ/ that lies mostly in the central part of the tongue employed, and an interesting difference, that is related to the height of the vowel and the level of jaw dropping, much higher than in Spanish, although they are both mid-to-low vowels. And still, it appears to me -and this is a very personal appreciation- that it is not jaw-dropping alone that makes our RS /a/ different from GB /ʌ/. And my teaching of the sound over the years has also proven to me that jaw-dropping alone does not do the trick.

It may or it may not make sense to teach the exact quality of this sound to RS speakers, and it will depend on whether the focus of the lesson is on accentedness or on intelligibility, but the truth is that for an RS speaker, there needs to be a contrast between the three different qualities making up the contrast STRUT-TRAP-BATH in English, which to RS speakers may be only subsumed into one.

So the next part of this post, coming up in a new weeks, I will present some "tips and tricks", rooted on some phonesthesic ideas, and also on realia techniques, that may help RS speakers turn their Spanish /a/s into STRUT.

After-post addition:

A reader rightly pointed out that I have not presented audio examples of my own of the difference between both sounds. So this is how I pronounce Spanish /a/ and English /ʌ/, and below you will find two Praat captures of the spectogram and formants of the same versions:

|

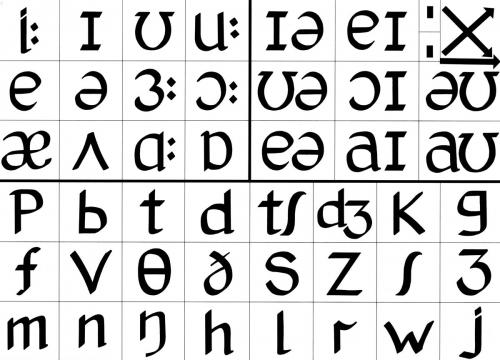

| Adrian Underhill's phonemic chart. (I would probably do away with the centring diphthongs as they stand, using /ɛ:/ for /eə/ and maybe still keep /ɪə/) |

I have completely embraced Adrian's belief and knowledge that "pronunciation is physical", and this motor side of pronunciation and our awareness of articulation through the different "buttons", as he calls them, is essential. However, out of his presentations, my independent reading, and my own teaching style, I have found that part of the process of acquisition of L2 features also lies on the images that we make of what the L2 features sound like.

Over the years, I have discovered that part of the fine-tuning processes we need to carry out to learn the sounds of L2 also involve affective aspects, including our own affective memory, and feelings. I have experienced situations in which students appear to be making the right articulatory movements, and still, there is something in the quality of the sound that does not "sound right". And in those cases, what I noticed is that it is the recourse to mental and affective images related to the sounds that appear to do the trick, rather than just the right lip or jaw position.

So in this post (which is, obviously, not a report on experimental research, so don't expect it to be so!), I will be going over a few techniques that I have used to include phonesthesia and realia in my pronunciation teaching. My focus this time will be on the STRUT vowel, /ʌ/, one which gave me a lot of trouble as a learner!

I will be covering a few different theoretical and practical areas on this post, which is why it will be divided into two:

Part 1:

- Speech Perception theories: a review with links to further reading materials.

- English vowel STRUT /ʌ/and Spanish vowel /a/: a review.

Part 2:

- Tips and tricks to teach STRUT

- Articulation

- Realia

- Phonesthesia

***

Images, Categories, and Speech Perception Theories

When writing my research paper for my specialisation course in Phonetics I in 2006, I came across a huge number of acquisition and psycholinguistic theories which really helped me to make sense of and inform my teaching practices. Even though I am not an expert in acoustic or perceptual matters, I believe that some basic knowledge of theories of Speech Perception can actually aid our comprehension of what happens to our learners when faced with L2 pronunciation challenges.

Speech Perception Theories state that perception is categorical and not continuous (Liberman, 1985), that is, we perceive categories, no matter whether there is individual variation, and thus, we group sounds according to our perception. We can, in other words, say if a certain set of sounds are the same, or if they are different, despite the realisational differences of those sounds. The Perceptual Magnet Effect theory by Kuhl (1991) addresses similar issues for vowel sounds, by exploring in more detail how we can perceive the space or distance between the different variants we hear, to somehow establish what degrees of variation can be significant for us to associate a certain sound or stimulus to either another category, or to a "bad" (so to speak!) version of the category under scrutiny. This all appears to work pretty well for our L1, though there are a few "traps", as the McGurk effect reveals, when the information that the different senses provide do not appear to match:

If anything, the McGurk effect proves that we draw information from different multimodal sources, which is a very useful thing to know for those of us who train in L2 perception and production!

Now, when it comes to perception of L2 sounds, the "same-different" categorisation may fail, as we tend to interpret our L2 sounds from our own L1 targets, as Flege's Speech Learning Model (1995) states. So if we consider Kuhl's and Flege's models, we can predict that certain L2 qualities, if close to certain L1 targets, will be perceived as similar, and thus, learners may take longer to acquire them and create new categories for them.

Our learners, then, may create a mental image of what a particular L2 segment sounds like in the light of their already-existing images of the sounds in their L1. This means that in order to improve perception and production, we need to create new images and categories that will establish a perceptual distance between L1 and L2 sounds.

So in this post, I would like to explore the fact that one of the ways in which we can displace the L1 images in favour of L2 categories is by creating images that may exceed the information that the visual and tactile senses can give us for the articulation of the sound, and even the auditory information we can initially get. I would like to propose ways in which affective and visual memories can activate these new sounds in the shape of perceptual images.

***

The STRUT /ʌ/ vowel in General British

Cruttenden (2014:122) describes the STRUT vowel as a "centralised and slightly raised CV [a]" and he acknowledges the presence of a back-er quality [ʌ̞̈] in Conspicuous General British speakers, though this quality also appears to be heard more often in GB (I agree! See below). The jaws are said to be separated considerably, and the lips, neutrally open. There is an MRI of a phrase containing STRUT in Gimson's.... companion website here.

Collins and Mees (2012) have defined STRUT as a central, open-mid checked vowel, and admit a certain degree of variation, but especially in terms of fronter qualities. In much the same way, Mott (2011:117) describes STRUT as being "slightly forward of centre, just below half open, unrounded".

The abovementioned authors would then place STRUT somewhere around these areas:

|

| Dark purple: STRUT, according to Mott & Collins and Mees. Light purple: Cruttenden (2014) and the backer quality [ʌ̞̈] he describes as a variant. |

Geoff Lindsey has a great post called "STRUT for Dummies" with a myriad audio examples that illustrate his comments on the historical and present variation of STRUT, wavering between [ə] and [ɑ]-like qualities.

Many Argentinian colleagues and I believe that STRUT appears to be moving closer now to an [ɑ] quality, at least for many young speakers. I cannot claim to have the knowledge or "ear" that Lindsey happens to be blessed with, but here's an example of what I believe I hear pretty often:

Compare this young YouTuber Zoella's versions of "love", "until", "one", "somebody", "bump", "tummy", "just", "hundred". Apart from being great examples of intra-speaker variation (I personally don't hear all the versions of the word "love" with the same STRUT quality), there are some other interesting processes going on . (Also, a great taste of the kind of TRAP vowel I hear now, so different from General American versions!).

(BTW, according to Wikipedia, Zoella is from Wiltishire, and currently living in Brighton. What would you say her accent is?)

If we see these variations in acoustic terms (disclaimer: not at all my area of expertise...yet!), we can find in Rogers (2000) there is a table presenting formant values for RP vowels, based on a measurement of adult male speakers in Gimson, 1980. In that measurement, RP /ʌ/ has got the following values:

F1: 760 Hz

F2: 1320 Hz

( Confront with the values that the study by Wells in his 1962 study had established F1:722, F2: 1236 )

(BTW, in simple terms, F1 inversely represents the articulatory tongue height, so that its higher frequency value represents lower tongue height. F2 represents degrees of backness, with lower values representing back-er vowels).

A study conducted by Hawkings and Midgley (2005) in four different age groups found the following mean formant values for these age groups:

If you are interested in pursuing this further, there are some interesting studies by

Ferragne and Pellegrini (2010), measuring vowels in 13 British accents.

Sidney Wood (SWPhonetics) analysis of different RP speakers' vowels across time.

If we see these variations in acoustic terms (disclaimer: not at all my area of expertise...yet!), we can find in Rogers (2000) there is a table presenting formant values for RP vowels, based on a measurement of adult male speakers in Gimson, 1980. In that measurement, RP /ʌ/ has got the following values:

F1: 760 Hz

F2: 1320 Hz

( Confront with the values that the study by Wells in his 1962 study had established F1:722, F2: 1236 )

(BTW, in simple terms, F1 inversely represents the articulatory tongue height, so that its higher frequency value represents lower tongue height. F2 represents degrees of backness, with lower values representing back-er vowels).

A study conducted by Hawkings and Midgley (2005) in four different age groups found the following mean formant values for these age groups:

- F1:630 -F2:1213 for over 65s (higher than the previous studies mentioned, and a bit backer)

- F1:643 F2:1215 for those speakers between 50-55 (lower than the over 65s, but equally central-back)

- F1:629 F2:1160 for speakers in the age range 35-40 (higher than those 10 years older, and backer)

- F1:668 F2:1208 for speakers aged 20-25 (lower than the other groups, but not as back as those speakers a bit older)

So according to this study, in comparison with the previous measurements reported, it would appear to be the case (at least for the speakers surveyed) that younger generations have a lower, and to a small degree, back-er STRUT than older generations).

If you are interested in pursuing this further, there are some interesting studies by

Ferragne and Pellegrini (2010), measuring vowels in 13 British accents.

Sidney Wood (SWPhonetics) analysis of different RP speakers' vowels across time.

***

Riverplate Spanish Vowel /a/

A contrastive analysis between General British and Riverplate Spanish (RS), and also the contributions of Speech Perception theories would lead us to expect that those students with RS as L1 are very likely to interpret English STRUT in the area of Spanish /a/ (not to mention distributional differences!). (BTW, in 2013 I attended a talk by Andrea Leceta at the III Jornadas de Fonética y Fonología, in which a comparative and experimental study on these features had been made, and the results confirmed these expectations. The proceedings have not yet been published, I am afraid.)

García Jurado and Arenas (2005) discuss Riverplate Spanish /a/ as having a wide degree pharyngeal of constriction (following the studies by Fant (1960) that focus the analysis of vowels based on the levels of constriction along the vocal tract) and clear oral opening and lack of lip rounding. They establish a mean F1:800 and F2:1200 values, which appear to match the degree of backness found for current versions of STRUT, though Spanish /a/ is much lower than English /ʌ/.

|

| Location of Spanish /a/ by Mott (2011) |

You can see a cross-section of the articulation of /a/in Spanish and in English in these captures from the University of Iowa's Sounds of Speech app.

Spanish /a/

(American) English /ʌ/

***

There appears to be an interesting similarity between Spanish /a/ and GB English /ʌ/ that lies mostly in the central part of the tongue employed, and an interesting difference, that is related to the height of the vowel and the level of jaw dropping, much higher than in Spanish, although they are both mid-to-low vowels. And still, it appears to me -and this is a very personal appreciation- that it is not jaw-dropping alone that makes our RS /a/ different from GB /ʌ/. And my teaching of the sound over the years has also proven to me that jaw-dropping alone does not do the trick.

It may or it may not make sense to teach the exact quality of this sound to RS speakers, and it will depend on whether the focus of the lesson is on accentedness or on intelligibility, but the truth is that for an RS speaker, there needs to be a contrast between the three different qualities making up the contrast STRUT-TRAP-BATH in English, which to RS speakers may be only subsumed into one.

So the next part of this post, coming up in a new weeks, I will present some "tips and tricks", rooted on some phonesthesic ideas, and also on realia techniques, that may help RS speakers turn their Spanish /a/s into STRUT.

After-post addition:

A reader rightly pointed out that I have not presented audio examples of my own of the difference between both sounds. So this is how I pronounce Spanish /a/ and English /ʌ/, and below you will find two Praat captures of the spectogram and formants of the same versions:

|

| My Spanish /a/ |

|

| My English /ʌ/ |

Etiquetas:

contrastive analysis,

ELT,

errors,

interlanguage,

production,

psycholinguistics,

sounds of English,

sounds of Spanish,

tricks

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)