Hi! My two previous posts (Part 1 - Part 2) reviewed the first four pronunciation myths, debunked by well-known pronunciation and phonetics specialists in the book "Pronunciation Myths", edited by Linda Grant. This post will mark the end of the review of this enriching, thought-provoking, book. Remember this is an informal review, with a few intrusive observations and reflections of my own.

(Warning! This is a very long post, so you may want to bookmark it for later reading.)

(Warning! This is a very long post, so you may want to bookmark it for later reading.)

***

Myth 5: Students would make better progress in pronunciation if they just practiced more - Linda Grant

This chapter begins with a reference to the film "The King's Speech", and an "inconvenient truth" : "long term speech characteristics can become an integral part of who we are" (Grant, 2014, "In the Real World", para. 5), which is why many people decide, consciously or unconsciously, not to introduce any changes to their accent. Citing Dalton and Seildhofer (1994:72), Grant reminds her readers that there is no "one-to-one relationship between what is taught and what is learned" when it comes to pronunciation. (And yes, we know that too well!)

The next section discusses aspects which have always been present in the debate around second language pronunciation, such as the role of age. Different studies are described which prove and also refute the effects of the Critical Period Hypothesis (Lenneberg, 1967) as far as the issue of accentedness is concerned. Grant believes the research in fact shows that it is social and psychological factors rather than neuro-biological changes that make the utmost difference in the end.

Another construct reviewed in this chapter is Lado's Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis. Some studies reported found that students whose L1 was similar to English had more English-like accents, but it was also reported that L1-L2 differences sometimes promote learning (in-keeping with Major's Similarity-Dissimilarity Hypothesis), since these are at times more perceptually salient than similarities. Grant finishes this section by revisiting the concepts of positive and negative transfer, both presented as inevitable processes in L2 pronunciation acquisition.

Grant later examines the role of exposure and use of L2 as a positive contribution to a learner's pronunciation achievement, especially in terms of fluency and comprehensibility. The other big factor was length of residence, though it was proven that it was not as effective as the actual frequent use of L2 outside the classroom.

The following aspect reviewed by Grant is the role of psycho-social factors in the attainment of L2 pronunciation. Issues of identity, motivation, attitude and inhibition are discussed in this section. Studies reported include those examining the roles of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, issues of allegiance to their own L1 ethnic group, and identification. I personally believe this is THE issue to consider when it comes to success in pronunciation learning.

The author recaps then some of the most important factors related to the attainment of an L2 pronunciation, but concludes that research has not yet established what is the relative impact of each of these variables: "age at the onset of learning, similarities between L1 and L2 phonologies, extent of exposure to and use of the L2, and affective factors (...), aptitude and natural talent". The research reviewed, however, does give teachers some basic information as to what aspects affecting L2 pronunciation can be addressed, and need to be tackled. (See my post on pronunciation goals for my own take on this)

Grant draws her chapter to a close by providing some practical suggestions: a) set realistic goals in partnership with our learners, giving more room to intelligibility over accentedness, and engaging students in setting their own personal goals; b) set interim goals to sustain student motivation throughout the course. This second point refers to what Wong (1987:8) has found regarding pronunciation achievement: "dramatic changes in student speech in 3 to 6 months are rare". (Well, I would personally have to read the study, because in my context this does not hold true at all. I guess this is true for a particular number of contexts with a specific set of characteristics...But I do grant them that my lessons are entirely pronunciation-based...). I do agree, however, that short-term goals, clear focus on specific features and assessable targets are a great "carrot and stick" for students not to give up. Suggestion c): increase student engagement by individualising assignments. Oh, yes. As I always say, "pronunciation teaching is a craft". There is a lot we can do with our students as a group, but there is an awful lot we need to do with our students on an individual basis. In this respect, Grant includes self-assessment sheets and rubrics for students to grade their own recorded assignments, for example. Suggestion d): ask students to maintain pronunciation logs. Even though Grant mentions examples that affect learners in which learners can use English outside the classroom, it is true that keeping track of the changes, breakdowns and challenges one encounters in the process of learning pronunciation is a great way to see how the process unfolds. I would have loved to have a diary for my Lab 1 course, I would have loved to see how I personally felt about having to "unlearn" my Spanglish accent and my own mental view of what English was like to get to the less Spanglish accent I have now (I have been listening to my Lab 1 cassettes, though...). Suggestion e): Maximise student exposure to English outside the classroom. This set of ideas includes ways in which we can introduce home practice as well using websites.

A final observation includes the importance of giving considerable amount of time to pronunciation instruction in the classroom, thus the need for integration for it to be an everpresent priority.

***

Myth 6: Accent reduction and pronunciation instruction are the same thing. By Ron Thomson.

This chapter warns the readers of the dangers of falling into advertising traps when it comes to selecting your tutors for accent reduction clinics or courses. By means of a few anecdotes, Thomson clarifies that many immigrants fall prey to deceit because they erroneously believe it is their accent that impedes successful communication and/or integration, whereas "L2 learners' perceived need for accent reduction is often the result of factors unrelated to pronunciation".

The premise to this chapter is that accent reduction and pronunciation instruction are different things, and for this, Thomson quotes Derwing and Munro (2009) with their description of three approaches to characterise programs as following a a) business, b) medical or c) educational model. Accent reduction is generally associated with the business model, accent "modification" with the medical approach, and pronunciation instruction with the latter.

The rest of this chapter reviews a considerable number of Google searches and website descriptions of the language used and the underlying assumptions of a few services offering pronunciation instruction or accent reduction services, some of which are compared to programmes that offer "miracle diets" (Lippi Green, 2012), and go unregulated. The review of programmes includes details of materials, costs, instructor qualifications and claims, which show how vast the offer is, and how confusing advertising could be in some cases. The chapter ends with a few proposals, including the need for provision of "ethical pronunciation instruction" that shows understanding of psycholinguistic, social and personal dimensions of foreign accent. Another major suggestion is that teachers "give more attention to pronunciation instruction as part of English language classes" and also to propose language programs to hold "stand-alone" pronunciation courses if possible. The discussion of this section ends with a set of practical tips as to how to avoid "charlatans".

This chapter left me thinking about a huge number of things. I find myself in a context in which I would say we do "accent modification" or "accent reduction", even, but our model is educational in nature, as we train teachers-to-be. Instruction in our context is carried out by specialised professionals, and the focus is mostly towards a native-like accent (pretty much in the same way other subjects attempt to help students to reach a native-like grammar or use of lexis...), while also training teachers to teach for different purposes (or so I hope). I guess we are all truly aware of the claims to the impossibility of reaching a native-like accent -we, pronunciation teachers, I think, are the best pieces of evidence for that, however obsessive we might be about our accents-, but even so, in our teacher-training context, we have many students who want to reach native-like proficiency (and many who do not, of course), and we work with them towards this goal (yes, there is a lot I could say and be critical about regarding this and a million other issues, but not today!) . I have to say I am lucky to be in a group of institutions in which I have the opportunity to do serious pronunciation instruction work and provide one-to-one moments of feedback, in spite of large classes. As I always say, pronunciation teaching is a craft, it cannot follow a "one-size-fits-all" model, since what works for one student may not work for the other. We can provide tools to the whole group of students, but feedback and fine-tuning practices need to be individualised and I hope this is something I can pass on to my students with my own feedback practices.

***

Myth 7: Teacher Training programs provide adequate preparation in how to teach pronunciation, by John Murphy.

This particular chapter is closely related to my current context, as I am a teacher trainer myself. For some reason, I never seem to find a book on pronunciation that will keep me "happy", though there are some good materials out there (my personal favourite being Celce-Murcia, Brinton and Goodwin, 1996, 2010) There is always something "missing" in these materials, something that drives my teacher trainees to be good, creative task designers, but at times "poor systematisaters". I try to make it my job to train teachers to actually make the presentation of features right, since after all, no matter how creative a task can be, if the teaching of the feature is not successful or well planned, the whole class plan will very likely fail anyways.

Now, off to the chapter. Murphy begins by retelling a personal experience teaching at a MATESOL course. One of the findings Murphy made in this journey is that pronunciation needs to be taught "within a framework of spoken communication". The author's account serves to introduce the question of confidence and knowledge that teachers may or may not feel they have when it comes to pronunciation teaching.

The research cited by the author includes issues of "teacher cognition" as a fundamental part of what should be the knowledge base for teaching, which includes, of course, knowledge about language, knowledge about second language acquisition, and specialist recommendations about pronunciation teaching. I think Murphy introduces a very important point here, that of the need to dive into teachers' beliefs, perceptions and understandings in order to help them build effective pronunciation teaching practices.

The author includes a table of research reports carried out by different experts and authors in different countries using different instruments, which in turn inform the report Murphy is introducing in this chapter. Some of the key points reviewed regarding teacher cognition include: a) teachers feel unprepared to teach pronunciation because of lack of training; b) there should be a clear focus on the pedagogical aspects of pronunciation teaching; c) previous experiences learning foreign languages have a bearing on the way teachers approach (or not) pronunciation teaching; d) teachers should be introduced to ways of teaching assessing pronunciation for intelligibility, introducing modern technologies and working on integration to the general ESL lesson.

I need to digress again, since this touches directly into my context. I lecture at three Teacher Training Colleges, and in all three, trainees are exposed to a minimum of two, and a maximum of seven (!) periods a week purely devoted to Phonetics and pronunciation, and in the last two years of the course of studies, also to pronunciation teaching. In two of these colleges, teachers have stand-alone pronunciation courses in all four years of training. That is an awful lot (and I am grateful, because it does show in most of trainees' pronunciation), but I sometimes fear these students may not still know how to approach pronunciation in their lessons in spite of all the input. At times, it is just a matter of giving teachers a few tricks and principles to "light the match", (and see the sparks in their eyes appear! Oh, joyful moment!), together with some consciencious reading of pedagogy and acquisition, and a "trip down memory lane" to their own experience learning the accent, but in some other occasions, I find teachers still get really "petrificus totalus" (yes, another HP reference) about this whole pronunciation teaching business. So much to think about....Anyway.

Murphy quotes Borg (2003, 2009) and eight findings on teacher cognitions, which is worth direct citation since they are spot on, in my opinion:

|

| Murphy (2014) in Grant (ed). Amazon Kindle Edition: Position 3272 of 4350 |

There is another interesting reference, to Gregory (2005) this time, which describes the fact that teachers are rarely given the chance to immediately apply in real classrooms, or even among peers, all the declarative knowledge they attain.

The last sections of this chapter contain fantastic remarks for us, non-native speakers of English who have trained as FL teachers. Murphy reminds us that our training in pronunciation as learners will help us understand what our learners are going through. Our own learned accent can be interesting and relevant models for our students, as long as it is intelligible, comprehensible, and only if the teacher is "aware of what some of the more prominent accented characteristics of his or her own speech could be" (oh, yes, I have my own list!)

The chapter presents a few suggestions as to what can be done in training programmes, and also a review of resources for pronunciation teaching and practice which are worth exploring, also listed as an appendix. A second appendix describes sample topics and syllable tasks that can be applied at graduate level. (Not to be missed!)

***

Epilogue to the Myths: "Best Practices for Teachers", by Donna Brinton

Brinton opens the epilogue by referring to a personal anecdote that supports her belief that we interpret the stream of speech in the foreign language by referring to our L1 and other languages we may have learned; and also that learners tend to process lexical chunks at the level of syllables/words/phrases, rather than phonemes.

This final section also introduces a very interesting list of "core knowledge and skills needed for L2 teachers to address pronunciation in the classroom", collected by Chan, Goodwin and Brinton in 2013. The list includes conceptual, descriptive and procedural knowledge, and it is truly worth reading (there is a copy of this list, presented by the authors at CATESOL 2013, here).

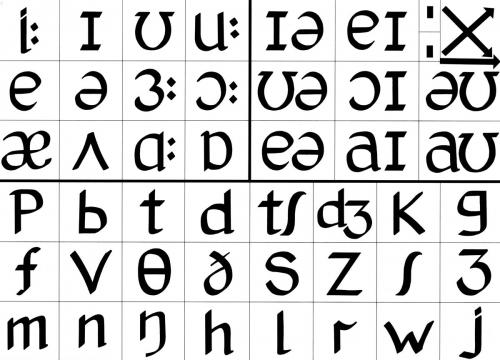

A second gift to the reader by Brinton: A summary of ideas and "best practices", including: a) the connection and separation of the concepts of intelligibility and accentedness, and a list of features contributing to the former that need to be trained in the classroom; b) the fact that not all pronunciation features have the same relevance for intelligibility; c) the finding that segmentals are critical building blocks of the sound system, but they need to be taught in terms of intelligibility needs, and also guided by functional load concerns; d) the tendency that claims that L2 adult learners may not reach an "accentless", native foreign accent; e) the fact that pronunciation learning is different from the learning of grammar or vocabulary, as it involves other modalities; e) the need to recognise the relation between perception and production, which is why it is important to introduce awareness raising activities to build new perceptual categories; f) the awareness that explicit and targeted feedback is truly beneficial; g) success in pronunciation learning depends on a myriad of factors, including age, motivation, identity, exposure, opportunities for real practice outside the classroom , and these need to be considered in our planning; h) L1 does have an influence on our acquisition of L2 pronunciation; i) exposure to authentic language is essential, including an analysis of processes of connected speech, that show the reality of speech "out there".

***

And so my review ends. My verdict? Pronunciation Myths is... a really insightful book, with discussions that probably describe pronunciation teaching issues worldwide, and a few other points and claims that can be questioned if seen from different locations and instructional contexts. A wealth of ideas, tips and tricks. And more importantly, in my opinion, a huge reference list of experimental, bibliographical, educational and also informal research that does not only "preach to the converted" (as a friend always says), but which may also, hopefully, persuade the sceptics, and the fearful.

.jpg)