|

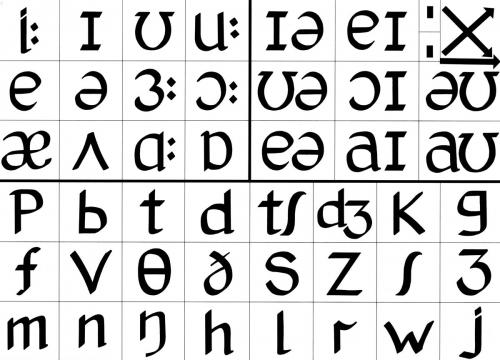

| Adrian Underhill's phonemic chart. (I would probably do away with the centring diphthongs as they stand, using /ɛ:/ for /eə/ and maybe still keep /ɪə/) |

I have completely embraced Adrian's belief and knowledge that "pronunciation is physical", and this motor side of pronunciation and our awareness of articulation through the different "buttons", as he calls them, is essential. However, out of his presentations, my independent reading, and my own teaching style, I have found that part of the process of acquisition of L2 features also lies on the images that we make of what the L2 features sound like.

Over the years, I have discovered that part of the fine-tuning processes we need to carry out to learn the sounds of L2 also involve affective aspects, including our own affective memory, and feelings. I have experienced situations in which students appear to be making the right articulatory movements, and still, there is something in the quality of the sound that does not "sound right". And in those cases, what I noticed is that it is the recourse to mental and affective images related to the sounds that appear to do the trick, rather than just the right lip or jaw position.

So in this post (which is, obviously, not a report on experimental research, so don't expect it to be so!), I will be going over a few techniques that I have used to include phonesthesia and realia in my pronunciation teaching. My focus this time will be on the STRUT vowel, /ʌ/, one which gave me a lot of trouble as a learner!

I will be covering a few different theoretical and practical areas on this post, which is why it will be divided into two:

Part 1:

- Speech Perception theories: a review with links to further reading materials.

- English vowel STRUT /ʌ/and Spanish vowel /a/: a review.

Part 2:

- Tips and tricks to teach STRUT

- Articulation

- Realia

- Phonesthesia

***

Images, Categories, and Speech Perception Theories

When writing my research paper for my specialisation course in Phonetics I in 2006, I came across a huge number of acquisition and psycholinguistic theories which really helped me to make sense of and inform my teaching practices. Even though I am not an expert in acoustic or perceptual matters, I believe that some basic knowledge of theories of Speech Perception can actually aid our comprehension of what happens to our learners when faced with L2 pronunciation challenges.

Speech Perception Theories state that perception is categorical and not continuous (Liberman, 1985), that is, we perceive categories, no matter whether there is individual variation, and thus, we group sounds according to our perception. We can, in other words, say if a certain set of sounds are the same, or if they are different, despite the realisational differences of those sounds. The Perceptual Magnet Effect theory by Kuhl (1991) addresses similar issues for vowel sounds, by exploring in more detail how we can perceive the space or distance between the different variants we hear, to somehow establish what degrees of variation can be significant for us to associate a certain sound or stimulus to either another category, or to a "bad" (so to speak!) version of the category under scrutiny. This all appears to work pretty well for our L1, though there are a few "traps", as the McGurk effect reveals, when the information that the different senses provide do not appear to match:

If anything, the McGurk effect proves that we draw information from different multimodal sources, which is a very useful thing to know for those of us who train in L2 perception and production!

Now, when it comes to perception of L2 sounds, the "same-different" categorisation may fail, as we tend to interpret our L2 sounds from our own L1 targets, as Flege's Speech Learning Model (1995) states. So if we consider Kuhl's and Flege's models, we can predict that certain L2 qualities, if close to certain L1 targets, will be perceived as similar, and thus, learners may take longer to acquire them and create new categories for them.

Our learners, then, may create a mental image of what a particular L2 segment sounds like in the light of their already-existing images of the sounds in their L1. This means that in order to improve perception and production, we need to create new images and categories that will establish a perceptual distance between L1 and L2 sounds.

So in this post, I would like to explore the fact that one of the ways in which we can displace the L1 images in favour of L2 categories is by creating images that may exceed the information that the visual and tactile senses can give us for the articulation of the sound, and even the auditory information we can initially get. I would like to propose ways in which affective and visual memories can activate these new sounds in the shape of perceptual images.

***

The STRUT /ʌ/ vowel in General British

Cruttenden (2014:122) describes the STRUT vowel as a "centralised and slightly raised CV [a]" and he acknowledges the presence of a back-er quality [ʌ̞̈] in Conspicuous General British speakers, though this quality also appears to be heard more often in GB (I agree! See below). The jaws are said to be separated considerably, and the lips, neutrally open. There is an MRI of a phrase containing STRUT in Gimson's.... companion website here.

Collins and Mees (2012) have defined STRUT as a central, open-mid checked vowel, and admit a certain degree of variation, but especially in terms of fronter qualities. In much the same way, Mott (2011:117) describes STRUT as being "slightly forward of centre, just below half open, unrounded".

The abovementioned authors would then place STRUT somewhere around these areas:

|

| Dark purple: STRUT, according to Mott & Collins and Mees. Light purple: Cruttenden (2014) and the backer quality [ʌ̞̈] he describes as a variant. |

Geoff Lindsey has a great post called "STRUT for Dummies" with a myriad audio examples that illustrate his comments on the historical and present variation of STRUT, wavering between [ə] and [ɑ]-like qualities.

Many Argentinian colleagues and I believe that STRUT appears to be moving closer now to an [ɑ] quality, at least for many young speakers. I cannot claim to have the knowledge or "ear" that Lindsey happens to be blessed with, but here's an example of what I believe I hear pretty often:

Compare this young YouTuber Zoella's versions of "love", "until", "one", "somebody", "bump", "tummy", "just", "hundred". Apart from being great examples of intra-speaker variation (I personally don't hear all the versions of the word "love" with the same STRUT quality), there are some other interesting processes going on . (Also, a great taste of the kind of TRAP vowel I hear now, so different from General American versions!).

(BTW, according to Wikipedia, Zoella is from Wiltishire, and currently living in Brighton. What would you say her accent is?)

If we see these variations in acoustic terms (disclaimer: not at all my area of expertise...yet!), we can find in Rogers (2000) there is a table presenting formant values for RP vowels, based on a measurement of adult male speakers in Gimson, 1980. In that measurement, RP /ʌ/ has got the following values:

F1: 760 Hz

F2: 1320 Hz

( Confront with the values that the study by Wells in his 1962 study had established F1:722, F2: 1236 )

(BTW, in simple terms, F1 inversely represents the articulatory tongue height, so that its higher frequency value represents lower tongue height. F2 represents degrees of backness, with lower values representing back-er vowels).

A study conducted by Hawkings and Midgley (2005) in four different age groups found the following mean formant values for these age groups:

If you are interested in pursuing this further, there are some interesting studies by

Ferragne and Pellegrini (2010), measuring vowels in 13 British accents.

Sidney Wood (SWPhonetics) analysis of different RP speakers' vowels across time.

If we see these variations in acoustic terms (disclaimer: not at all my area of expertise...yet!), we can find in Rogers (2000) there is a table presenting formant values for RP vowels, based on a measurement of adult male speakers in Gimson, 1980. In that measurement, RP /ʌ/ has got the following values:

F1: 760 Hz

F2: 1320 Hz

( Confront with the values that the study by Wells in his 1962 study had established F1:722, F2: 1236 )

(BTW, in simple terms, F1 inversely represents the articulatory tongue height, so that its higher frequency value represents lower tongue height. F2 represents degrees of backness, with lower values representing back-er vowels).

A study conducted by Hawkings and Midgley (2005) in four different age groups found the following mean formant values for these age groups:

- F1:630 -F2:1213 for over 65s (higher than the previous studies mentioned, and a bit backer)

- F1:643 F2:1215 for those speakers between 50-55 (lower than the over 65s, but equally central-back)

- F1:629 F2:1160 for speakers in the age range 35-40 (higher than those 10 years older, and backer)

- F1:668 F2:1208 for speakers aged 20-25 (lower than the other groups, but not as back as those speakers a bit older)

So according to this study, in comparison with the previous measurements reported, it would appear to be the case (at least for the speakers surveyed) that younger generations have a lower, and to a small degree, back-er STRUT than older generations).

If you are interested in pursuing this further, there are some interesting studies by

Ferragne and Pellegrini (2010), measuring vowels in 13 British accents.

Sidney Wood (SWPhonetics) analysis of different RP speakers' vowels across time.

***

Riverplate Spanish Vowel /a/

A contrastive analysis between General British and Riverplate Spanish (RS), and also the contributions of Speech Perception theories would lead us to expect that those students with RS as L1 are very likely to interpret English STRUT in the area of Spanish /a/ (not to mention distributional differences!). (BTW, in 2013 I attended a talk by Andrea Leceta at the III Jornadas de Fonética y Fonología, in which a comparative and experimental study on these features had been made, and the results confirmed these expectations. The proceedings have not yet been published, I am afraid.)

García Jurado and Arenas (2005) discuss Riverplate Spanish /a/ as having a wide degree pharyngeal of constriction (following the studies by Fant (1960) that focus the analysis of vowels based on the levels of constriction along the vocal tract) and clear oral opening and lack of lip rounding. They establish a mean F1:800 and F2:1200 values, which appear to match the degree of backness found for current versions of STRUT, though Spanish /a/ is much lower than English /ʌ/.

|

| Location of Spanish /a/ by Mott (2011) |

You can see a cross-section of the articulation of /a/in Spanish and in English in these captures from the University of Iowa's Sounds of Speech app.

Spanish /a/

(American) English /ʌ/

***

There appears to be an interesting similarity between Spanish /a/ and GB English /ʌ/ that lies mostly in the central part of the tongue employed, and an interesting difference, that is related to the height of the vowel and the level of jaw dropping, much higher than in Spanish, although they are both mid-to-low vowels. And still, it appears to me -and this is a very personal appreciation- that it is not jaw-dropping alone that makes our RS /a/ different from GB /ʌ/. And my teaching of the sound over the years has also proven to me that jaw-dropping alone does not do the trick.

It may or it may not make sense to teach the exact quality of this sound to RS speakers, and it will depend on whether the focus of the lesson is on accentedness or on intelligibility, but the truth is that for an RS speaker, there needs to be a contrast between the three different qualities making up the contrast STRUT-TRAP-BATH in English, which to RS speakers may be only subsumed into one.

So the next part of this post, coming up in a new weeks, I will present some "tips and tricks", rooted on some phonesthesic ideas, and also on realia techniques, that may help RS speakers turn their Spanish /a/s into STRUT.

After-post addition:

A reader rightly pointed out that I have not presented audio examples of my own of the difference between both sounds. So this is how I pronounce Spanish /a/ and English /ʌ/, and below you will find two Praat captures of the spectogram and formants of the same versions:

|

| My Spanish /a/ |

|

| My English /ʌ/ |