Hello, again! This is my last post on the Phonetics Teaching and Learning Conference at UCL (click to read parts 1 and 2 ). I will not be able to to report on all the content of every talk, so you'll have to excuse my selection. Any error (if any) is due to my low caffeine levels or lack of understanding of what the claims in the talks were, and I'm happy to make corrections if the authors point them out. And the proceedings will be available soon, so you will be able to read the full papers in a couple of months!

Andrej Stopar Perception of the General British vowels /ʌ/, /ɑ:/, /ɒ/, and /ɔ:/ by Slovenian speakers of English

Andrej Stopar Perception of the General British vowels /ʌ/, /ɑ:/, /ɒ/, and /ɔ:/ by Slovenian speakers of English

Stopar presented a continuation of his presentation in 2015, in which Slovenian speakers of English are reported to have participated in perception experiments on different English vowel contrasts after instruction. Slovenian vowels are very similar to Spanish, so I found the results quite interesting, since the vowel that appears to have given students more trouble is that in the LOT set. Stopar mentions a few errors that could actually be due to the fact that words and non-words were used (students choosing a THOUGHT vowel for the nonsense word "fot"). In general the perception pre-test results were quite good for one of the groups, but the biggest difference was made in the group whose pre-test had been quite weak.

Kakeru Yazawa, Mariko Kondo and Paola Escudero: "Modelling Japanese speakers' perceptual learning of English /iː/ and /ɪ/ within the L2LP framework". This talk discussed Escudero's model of Second Language Linguistic Perception for Japanese students working on American English vowels /iː/ and /ɪ/, and they discussed their results in the light of Boersma's (1998) Stochastic Optimality Theory, that unlike traditional OT sees a gradient (and not a categorical set) of ranking values and constraints and the perception process as a continuum that should not easily assign vowel perceptions to a particular phonological category.

Yumi Ozaki, Kakeru Yazawa and Mariko Kondo: "L2 English speech rhythm of Japanese speakers: An alternative implementation of the Varco metrics" Ozaki et al propose an alternative form of using the Varco metrics, because Japanese constraints render the use of the regular Varco metrics for vocalic and consonantal intervals as problematic. Instead of using the mean duration of intervals, they suggest an nVarco: using overal segmental durations. More proficient Japanese learners have been found to exhibit more variability in vocalic and consonantal duration.

Hui-Chuan Liu: "Identification of Mandarin high-level tone and high-falling tone by Vietnamese learners"

Liu discussed the problems that her Vietnamese learners had in the identification of two contrastive tones, high-level vs high-falling. Since Vietnamese tones have no large falling slopes, this tone brings about difficulty for those learning Mandarin. In her study, Liu found that duration of syllables had a bearing on the type of errors made by learners, but she recommended not using length as a teaching resource because it is not distinctive, nor reliable.

Eva Estebas-Vilaplana: "How imitation can help the acquisition of L2 pronunciation"

I love Estebas-Villaplana's presentations in general (and her book is so useful!), and even more so because she teaches at UNED, a distance learning uni in Spain. Teaching English pronunciation to Spanish speakers in distance education is a great challenge, so I was very curious about what she would be presenting this time. The experience that Estebas presented involved getting Spanish speakers to read a text in their own L2 English accent, and another version in an accented English version of Spanish (Spanglish or Englishñol, should I say?). Her students imitated English rhythm and reduction better in their "mock" versions, than in their real L2 English.

Estebas suggests using these "mock" Spanish accents to see what kinds of features students store in connection to how they believe English sounds, and use them to improve their L2 English accents.

For some years now, we have used this strategy in Buenos Aires for /t/ and /d/, and it worked quite well. Many of our students have access to accents of Spanish like Puerto Rico or singers like Ricki Martin, whose /t,d/ are alveolar, and that has proven useful. But I had never considered that students can also improve on rhythm using this strategy!

Yusuke Shibata, Masaki Taniguchi and Young Shin Kim: "A brief intensive method to help Japanese learners perform English tonicity" Shibata et al presented a few methods they have used to help learners acquire narrow focus. Basically, they worked on short exchanges like the ones in textbooks where there is verbatim repetition, and they trained learners in deaccenting repeated items. They tested them before and after instruction, and their improvement was considerable. Some audience members suggested doing a longitudinal study to see how much of this "sticks" some time after instruction, since the exchanges used to test were very short, and students may have got the hang of it strategically rather than actually learning about narrow focus.

Marina Cantarutti: "Questioning the teaching of “question intonation”: the case of classroom

elicitations" - My paper had two big parts: the first section consisted in reviewing the theory on 'question intonation' that you can find in the intonation textbook materials used at Teacher Training Colleges in Buenos Aires (Wells, Tench, Brazil, Baker...). Starting from their assumptions, and based on my prior experience of these materials being insufficient to account for the choices speakers make in different speech styles and genres, I did a short corpus study of Teacher Talk (one of the speech situations we train teachers on in their 3rd year), in particular, of teacher elicitations in the recitation stage. By making a conversation-analytic approach of turn-taking, sequencing, and embodied behaviour, I have found the role of "terminal" tone (the last tone in the question) to be related to epistemic assymetries and the handling of the turn-taking system, and not in any way related to the syntax of the question, or attitudinal approaches, neither to finding out or making sure concerns (unless we redefine these notions, something I mention in the full paper). My biggest claim is that we can no longer apply "one-size-fits-all" syntactic and attitudinal approaches to intonation, and that functional approaches work only if properly combining top-down generic analyses with bottom-up, local, turn-by-turn analyses.

Miriam Germani and Lucía Rivas: "A genre approach to prosody teaching intonation from a discourse perspective"

Miriam Germani and Lucía Rivas: "A genre approach to prosody teaching intonation from a discourse perspective"

I'm a big fan of Germani & Rivas' work, we are quite like-minded in our approaches to intonation teaching, and I was very lucky to work with them on different occasions. Germani and Rivas (as I did on my own preso) discussed the shortcomings of intonation textbooks, and the simplifications that these make, that create two common problems (that all of us who do real discourse intonation face!): a) students taxonomise but do not do any real discourse-functional study, they merely repeat classifications; b) students fail to see the contributions that intonation makes to textual organisation and interpersonal projections of meaning. By using Systemic Functional Linguistics, and following the basis in Martin & Rose's (2008) "Genre Relations", and the descriptions of intonation in Brazil and Halliday & Greaves, among others, Germani & Rivas have helped their students make better top-down, holistic descriptions of meaning in text, and have improved their students' accounting of intonation choices.

Hajar Binasfour, Jane Setter and Erhan Aslan: "Enhancing L2 learners’ perception and production of the Arabic emphatic sounds". Binasfour et al describe how the use of Praat can help learners improve on their perception and production of Arabic emphatic sounds, by teaching them how to identify pharyngealisation in spectrograms and compare their production of sounds to that of accurate Arabic emphatics.

Pekka Lintunen, Aleksi Mäkilähde and Pauliina Peltonen: "Learner perspectives on pronunciation feedback" Lintunen et al reviewed the results of an experience of peer and teacher-led feedback on pronunciation. There were some interesting findings, including the fact that students valued peer feedback for pronunciation, and that they trusted the feedback of their non-native teachers of English. Lintunen et al also made a point of the fact that pronunciation feedback-giving is different from other feedback practices, and so it needs to be taught to teacher trainees as a special skill.

Gladys Saunders What does the rapid spread of /u/-fronting in American English have to do with the teaching of French phonetics? Saunders mentions the now established process of GOOSE-fronting and the way this can be used as a reference point to learn specific French vowel sounds.

Daniela Martino: "Sequencing and technology–aided activities in the acquisition of foreign sounds" Martino presented a sequence of presentation and practice of phonetic and phonological features and a number of web platforms that she has used to help her trainees improve on their English pronunciation. The first stage was identification, and she used Sonocent AudioNotetaker (which Cauldwell has popularised), PlayPhrase.me (now down, unfortunately), and TubeQuizard, to create tasks and quizzes leading students to perceive processes such as weakening. Students are also invited to do transcriptions in IPA by using subtitling software. During the imitation stage, students use Soundcloud to record and upload their productions and they use the front facing camera of their mobiles to monitor their articulation. Martino has found the combination of these tools and this sequence to be effective for her students' progress.

Ana Cendoya: "Technology–aided pronunciation teaching in an ESP/EAP course" Cendoya described the techniques she uses to help her engineering students to improve on their pronunciation when making presentations. She mentioned the use of E-portfolios and strategies to build proprioception, and mentioned how students with time became less "resistant" to recording, and feedback.

Hsuehchu Chen and Qianwen Han: "A corpus-based online Mandarin pronunciation learning system for Cantonese learners: development, evaluation, and implementation" Chen et al described the new Mandarin corpus system (http://ec-concord.ied.edu.hk/mandarin_pronunciation/) and how by using its features, and Praat, they have helped their Cantonese learners improve on their pronunciation.

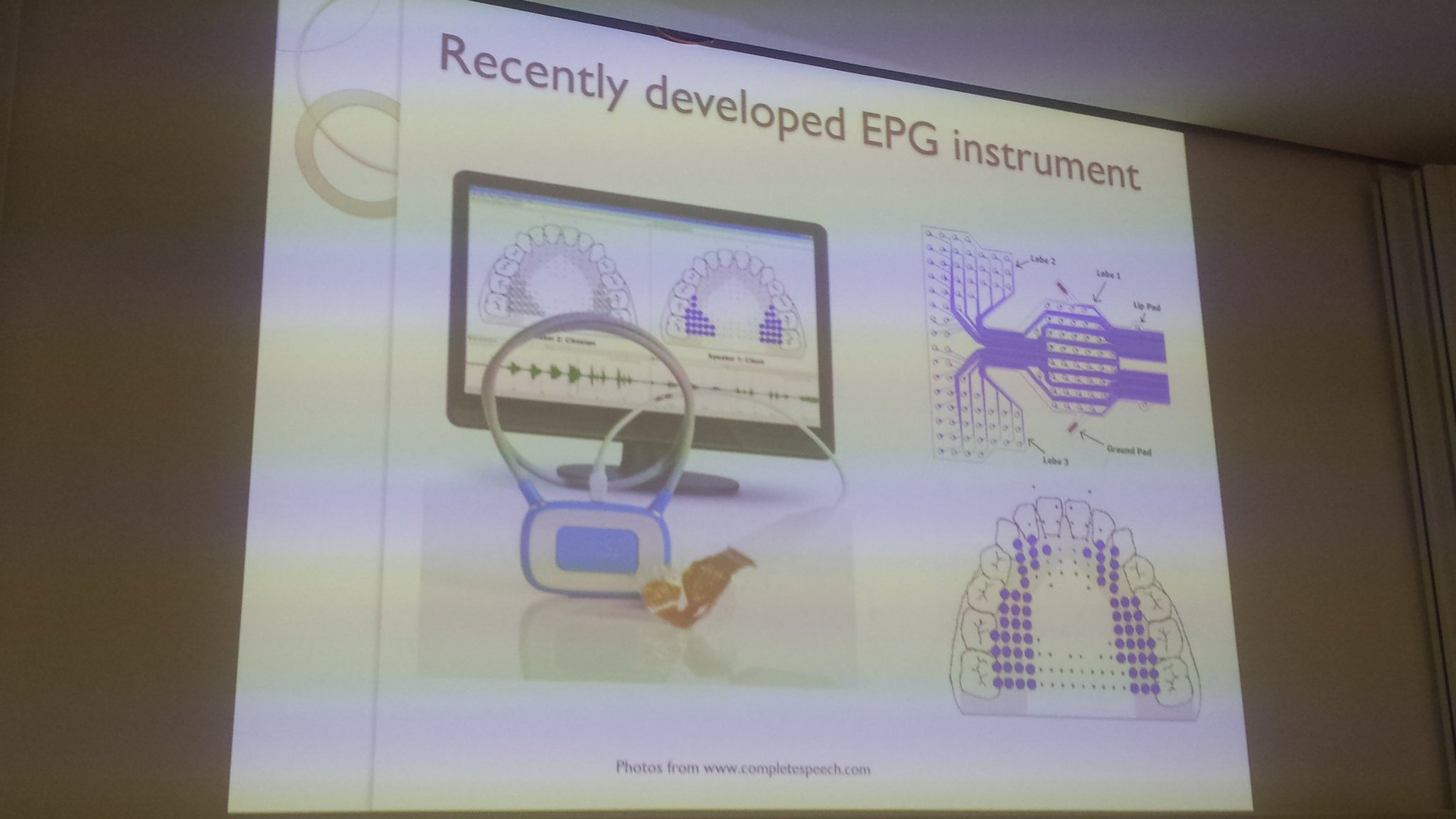

Shawn L. Nissen, Kate E. Lester, Laura Catharine Smith, Lisa D. Isaacson and Teresa R. Bell "Using electropalatography in second language pronunciation instruction: a preliminary examination of voiceless German fricatives" Nissen showed us the evolution of electropalatography through the ages, and displayed the newest technology, which has made access to these devices much cheaper. The experiment presented, though limited to a few participants, shows how the information derived from EPG may help learners fine-tune their sounds, especially when the differences between their production and the expected target are quite small.

|

| (Image credits: PTLC Twitter account) |

Lunch and coffee breaks were as enjoyable as the talks. PTLC seems like a small conference, but it has the right atmosphere, and UCL with all its phonetic history makes the perfect setting for this meeting. Unlike other conferences, PTLC requires in their call for papers that full papers (not abstracts) are presented, so if you are thinking of participating in 2019, get your research going today!

Thanks to Michael, Joanna and Molly for organising, and thank you for trusting me with paper reviews as well. It's been a fabulous experience, and I really hope I can present more interesting stuff in two years' time, when my own research will (hopefully!) have yielded some results!

Thanks to Michael, Joanna and Molly for organising, and thank you for trusting me with paper reviews as well. It's been a fabulous experience, and I really hope I can present more interesting stuff in two years' time, when my own research will (hopefully!) have yielded some results!